How we use React/Redux with TypeScript

Our team develops visual applications in the field of medical informatics. We started using React/Redux with TypeScript a few months ago. This post is a highly opinionated summary of best practices that evolved over time:

- Favor Types Over Classes

- Don’t Fear Stringly Types

- Favor Composition Over Inheritance

- Immutability FTW

- Nominal Typing

- Explicit Types Enhance Readability

- TSS: CSS + TypeScript = 😍

- Look Ma, No Semicolons!

A bit of personal background, to give certain decisions more context: I have been developing user interfaces for over 20 years. Java and OOP have been loyal companions throughout most of this time. A few years ago, I started doing more and more FP, mostly in Scala & Elm, but also in Java (hi vavr 👋).

Our team members come from all sorts of backgrounds. When deciding on a web app stack, opinions varied a lot. We finally settled on React/Redux + TypeScript as a compromise – it turned out to be a good decision.

Favor Types Over Classes

Coming from an OOP background, it was comforting that TypeScript brings familiar OOP constructs to the table. However, TypeScript is based on a structural type system, which can confuse Java developers very quickly:

class Patient {

firstName: string

lastName: string

constructor(firstName: string, lastName: string) {

this.firstName = firstName

this.lastName = lastName

}

}

const patient: Patient = { firstName: 'Ada', lastName: 'Lovelace' }

console.log(patient instanceof Patient) // false – seriously?! 🤔I am sure that one could get used to the TypeScript way of working with classes. However, we somehow ended up not using classes at all 🤷. Instead, we exclusively model our data with read-only types:

type Patient = Readonly<{

id: PatientId

caseId: CaseId

bed: BedId

firstName: string

lastName: string

}>Super concise and very safe to use.

Don’t Fear Stringly Types

Any experienced Java programmer avoids stringly types like the plague. In Java, this makes sense, they prevent the compiler from helping us find errors. The TypeScript compiler works differently, so be ready to embrace patterns which you would avoid in Java:

type Patient = Readonly<{

gender: 'male' | 'female' | 'non-binary'

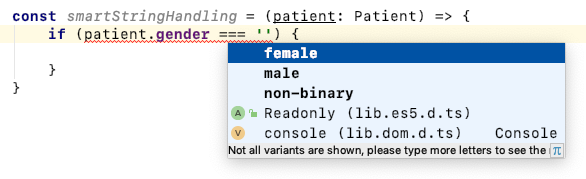

}>Code completion works perfectly fine here:

And the compiler detects errors flawlessly:

const smartStringHandling = (patient: Patient) => {

if (patient.gender === 'whatever') { // compile error

}

}To give a more advanced example, here’s how we base our action types, actions, and reducers on simple strings:

actionTypes.ts

const ADD_MESSAGE = 'message/add'

const ADD_TODO = 'todo/add'actions.ts

type Action = AddMessageAction | AddTodoAction

type AddMessageAction = Readonly<{

type: typeof ADD_MESSAGE

message: Message

}>

type AddTodoAction = Readonly<{

type: typeof ADD_TODO

todo: Todo

}>reducer.ts

const reducer = (state: State, action: Action): State => {

switch (action.type) {

case ADD_MESSAGE:

// 🎉 this would require a cast in Java

const message = action.message

return {

...state,

messages: state.messages.push(message)

}

case ADD_TODO:

return {

...state,

todos: state.todos.push(action.todo)

}

}

}Favor Composition Over Inheritance

As mentioned above, we don’t really use TypeScript’s OOP features, so using inheritance has never been very tempting. Instead, we often use a mix of composition, union types, and intersection types to foster code re-use:

type Patient = Readonly<{

address: Address // Composition

gender: 'male' | 'female' | 'non-binary' // Union Type

}>

type Displayable = Readonly<{

displayName: string

}>

type DisplayablePatient = Patient & Displayable // Intersection TypeImmutability FTW

We haven’t seen many runtime errors, but the ones that occurred were all caused by inconsistent mutations. That’s why we settled on using the immutable collections library to make all our state completely read-only:

import { Map } from 'immutable'

type State = Readonly<{

bedByPatient: Map<PatientId, BedId>

}>Nominal Typing

Using type aliases for your identifiers seems very convenient. No need for extra wrapping, and very readable code:

type PatientId = string

type BedId = string

type State = Readonly<{

bedByPatient: Map<PatientId, BedId>

}>Unfortunately, things look more type-safe than they are. Aliases are nothing more than what their name implies: they are simple synonyms. Any string can be used in place of a PatientId or BedId – and vice versa:

const state: State = {

bedByPatient: Map<PatientId, BedId>()

}

// Compiles just fine, which is NOT what we want

state.bedByPatient.set('foo', 'bar')We want to have types which can be distinguished by the compiler because they have different names, even though they share the same structure (a string). This is known as “nominal typing”. The TypeScript Deep Dive Book gives a good list of nominal typing patterns.

We are using the enum-based brand pattern to get the desired compile-time safety:

enum PatientIdBrand {}

type PatientId = PatientIdBrand & string

enum BedIdBrand {}

type BedId = BedIdBrand & string

type State = Readonly<{

bedByPatient: Map<PatientId, BedId>

}>

const state: State = {

bedByPatient: Map()

}

// Compile error:

// Argument type '"foo"' is not assignable to parameter of type 'PatientId'

state.bedByPatient.set('foo', 'bar')Explicit Types Enhance Readability

While it is often possible to not specify types explicitly, they still sometimes enhance code readability (and IDE completion, for that matter). Container components are a good example: they involve a lot of “plumbing”, where input/output types have to match, so explicit types are a plus here. This is how our container components tend to look:

type Props = Readonly<{

patientId: PatientId

}>

type FromStateProps = Readonly<{

patient: Patient

}>

const mapStateToProps = (state: State, props: Props): FromStateProps => {

const patient = getPatient(state, props.patientId)

return {

patient

}

}

type FromDispatchProps = Readonly<{

onMouseEnter: () => void

onMouseOut: () => void

}>

const mapDispatchToProps = (dispatch: Dispatch<PatientsAction>, props: Props): FromDispatchProps => {

return {

onMouseEnter: () => dispatch(selectPatients(ImmutableList.of(props.patientId))),

onMouseOut: () => dispatch(selectPatients(ImmutableList()))

}

}

export default connect(mapStateToProps, mapDispatchToProps)(ExampleComponent)TSS: CSS + TypeScript = 😍

As a developer, CSS has always been the scary corner of my applications. It uses a global namespace, you cannot use variables, and it’s almost impossible to tell which code is even in use at all. So you end up treating your CSS very differently from the rest of your code: no refactorings, no re-use, no clean-up.

We are using Material-UI in all our projects, so it did not take much convincing to also use their styling solution. It uses JSS at its core and has excellent TypeScript support. This is how a basic component looks:

import { createStyles, withStyles, WithStyles } from '@material-ui/core'

import * as React from 'react'

const styles = createStyles({

root: {

backgroundColor: 'steelblue'

}

})

type Props = Readonly<{

text: string

}> & WithStyles<typeof styles>

const ExampleComponent = ({ text, classes }: Props) =>

<div className={classes.root}>{text}</div>

export default withStyles(styles)(ExampleComponent)Look Ma, No Semicolons!

And finally, a good practice that is not specific to React nor TypeScript: make your code prettier! We use husky to kick off code formatting before each git commit. Here’s our current configuration:

.prettierrc:

Thanks for reviewing this post, Ben!